Was north Alabama forgotten in the days after tornadoes raked Alabama on April 27, 2011? It seemed that way.

“The thing I heard most from citizens that were affected was a frustration that they had sort of been overlooked and forgotten,” remembers National Weather Service Meteorologist Chris Darden.

Darden’s job then was to travel out from the Huntsville NWS office to assess damage after the storms. Today, he’s meteorologist in charge of that office.

Darden remembers talking to a man in the northeast Alabama town of Henagar “and he, in a very nice way, lamented the fact he had not seen anyone offer assistance or come by.”

Five years later, search the Web for “Alabama tornadoes April 27, 2011” and the first images you see are of Tuscaloosa, where an EF-4 tornado hit near the University of Alabama. It killed 66 people in Tuscaloosa County and next-door Jefferson County.

Tuscaloosa is where President Obama came two days later, and Tuscaloosa led the first national reports from Alabama. Typical was the National Geographic website’s April 29 headline about a “monster storm” in Tuscaloosa.

North Alabama was out of the spotlight, but it wasn’t ignored. It’s more complicated than that.

Details emerge slowly

In North Alabama as elsewhere in the state, details were slower to emerge. It took time to learn that two EF-5 tornadoes had crossed the area killing 98 people and scouring parts of five counties.

A flattened communications grid didn’t help. Power and telephone lines were down. All of Huntsville was blacked out, and power didn’t come back on until May 2. The Huntsville Times designed its April 28 newspaper with power from an RV’s generator.

“Keep in mind, the only thing they were hearing was on the radio,” Darden says of survivors. “We went to very few places that had power, at least the first week or so. All they were hearing about was the president coming to Tuscaloosa or other dignitaries.”

Overwhelming damage

Damage in North Alabama was so widespread the National Weather Service didn’t know a tornado had hit Bridgeport for three days, Darden says. It didn’t know until mid-May that an EF-2 tornado had passed near Fort Payne.

Meanwhile, people across the nation were watching the video of the Tuscaloosa tornado again and again. And it was amazing.

“There was the same video of the tornado that moved across Limestone County,” Darden says. “There was the same video of Cullman. For whatever reason, it didn’t get the same play. It didn’t affect the university.”

Overwhelmed responders

Beyond poor communications and damaged infrastructure, public and private response agencies were “overwhelmed,” in Darden’s words. It took days for the response to ramp up to the scale of the disaster.

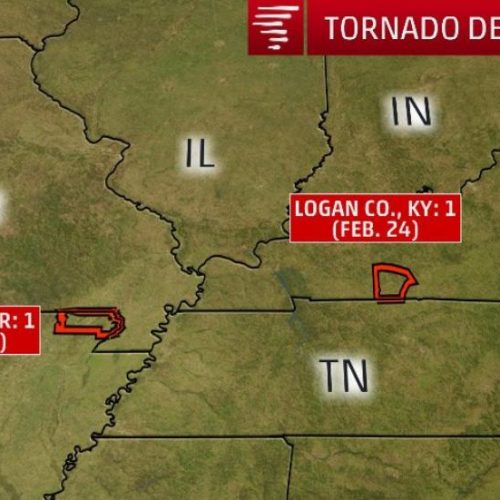

Meanwhile, the national story itself was soon bigger than Tuscaloosa or even Alabama. It was the story of a “super cell” outbreak spawning 199 tornadoes in Alabama, Mississippi, Georgia and Tennessee. In all, 324 people died.

And five days later on May 2, just as the power was coming back on in Huntsville, U.S. forces in Pakistan killed Osama bin Laden. The death and destruction in one section of one state became a secondary part of what was now the second-biggest story in America.

How bad was it in North Alabama? “The extent of the devastation was unparalleled,” the National Weather Service would say later, “with countless homes, neighborhoods and portions of cities either partially or completely destroyed. Houses were removed from foundations, churches were flattened and debris, livestock and people were thrown large distances through the air.”

University of Alabama in Huntsville meteorologist Tim Coleman told NASA science writer Dauna Colter that, “Brick homes were blown apart…. Some of these tornadoes were almost unsurviveable. Only in a well-built storm shelter would you make it through.”

Three quick stories

Darden tells three quick anecdotes to illustrate. In the first, he’s in Phil Campbell, where 20 people died and 800 structures were destroyed. It’s a Sunday afternoon just before crews are about to begin burning whatever’s left.

“I remember standing there, looking around, and there literally was not a single thing that was recognizable, not a car, a house, a mail box, nothing,” Darden says.

In the second story, Darden is in Higdon with a woman who saw the tornado, rushed home from a birthday party at a friend’s house and found her mother, father and younger sister dead.

“She was the first one on the scene,” Darden says. “She hadn’t left and hadn’t said hardly a word. We walked up and asked if we could take some photographs. ‘I’ve lost everything,’ she said. “I have nothing left.’ She started crying. That was really hard, really, really tough.”

The next street over, a woman and her two daughters stood in pile that used to be a farm house.

“There was literally nothing left,” Darden says. “They owned 40 head of cattle and had to put 21 down, not for puncture wounds, but impact wounds. They had been picked up and thrown by the tornado.”

North Alabama today

In North Alabama today, people understand what they survived. Roger Lingerfelt, who works for a telephone co-op, was a Rainsville city councilman then and still is today. His attitude is typical of what you find in the region.

Standing in front of his farmhouse in late March, Lingerfelt said he understands the early attention on Tuscaloosa and other areas. He doesn’t begrudge it a bit. Like others here, he focuses on pride at how his community and other utility and telephone co-ops rallied.

Volunteers did come from more than 20 states, said Tim Eberhart, executive director of the Rainsville Chamber of Commerce. They brought “a lot of food, a lot of water, and they were here for months” working hard to help people clean up and start over.

“The volunteers said they’d never come to a community like this,” Lingerfelt said. People, if they had anything at all for dinner, would say to take the donated meals down the road “to someone who needs it worse.”

Rainsville is back

Five years later, Rainsville is basically back. Only a few shattered trees mark the storm’s path north of town. Victory Baptist Church is whole again, and the DeKalb County Schools Coliseum is rebuilt and home to a monument to the 35 who died here.

But some psychological scars remain. Lingerfelt admits he called his insurance agent as this spring approached to check his home and property coverage – just to make sure.

“If the weather turns bad,” Linda Samples of Rainsville said, “it’s the first thing that pops into everyone’s head.”

People get on edge, Lingerfelt agreed, “and they want to be in the right places – safe places. Kids notice it. They get nervous.”

Celebrating recovery

Samples led the committee that built the memorial monument. “We worked on it every Saturday rain or shine,” she said. “Everyone wanted to help. People were making lunches, carrying blocks.”

There’s been a remembrance ceremony every April 27 since 2011, Samples said, but this year will be different.

“This year we will be celebrating the recovery,” she said. “We’ll be looking to the future.”

By Lee Roop | lroop@al.com

Email the author | Follow on Twitter

on April 18, 2016 at 5:45 AM, updated April 18, 2016 at 8:51 AM