One tornado tossed a car like a toy, another reduced buildings to rubble, a third shredded trees to splinters.

Three recent tornadoes hit three different states — New York, Oklahoma, and Maryland — yet no tornado warnings were issued before any of the twisters touched down.

Do we have a problem?

The National Weather Service, the federal agency that issues tornado warnings, says no. “There’s no headline here,” said Greg Schoor, acting severe weather program leader for the weather service, noting that they were all separate, unrelated events.

“They were three examples of low-end tornadoes, and are not representative of what’s going on nationally,” he said, referring to how well the agency does with tornado warnings overall.

This year alone, he said that all 22 EF-3 or EF-4 tornadoes — the ones at the high end of the intensity scale that wreak the most havoc — had warnings issued beforehand, Schoor said. “We don’t miss the big ones,” he said.

Nationwide, the weather service said that in the past nine years, 95% of all strong to violent tornadoes (EF-3 and above) have had warnings issued for them.

And if anything, the weather service issues many more false alarms for tornadoes than they do for actual twisters, with an annual average false alarm rate of about 75%.

The weather service is working to rectify this issue: “There has been a general trend to reduce the false alarm rates associated with tornadoes, which means you tend to be cautious when issuing a warning,” said meteorologist Roger Wakimoto, the president of the American Meteorological Society and vice chancellor for research at UCLA. “The rationale is that a false alarm rate that is high is similar to crying wolf too much — the public starts ignoring the warnings,” he said.

The three tornadoes in question all occurred during severe thunderstorm warnings, which is the catch-all term for any thunderstorm that can produce tornadoes, and/or large hail, and/or strong, damaging winds.

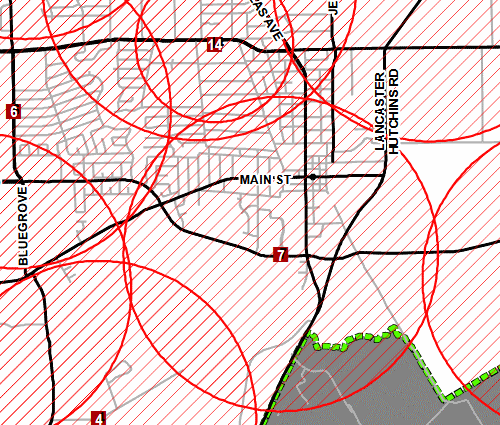

The three events were a group of four tornadoes on July 20, 2017, in western New York, with the worst damage in Hamburg and Orchard Park; three tornadoes that hit Tulsa on Sunday Aug. 6; and one that hit Salisbury, Md., on Monday, Aug. 7.

None of the tornadoes caused any fatalities, though about two dozen people were injured in the Tulsa storm.

The tornadoes were all “very hard to detect and no one’s fault,” said Marshall Shepherd, a meteorologist at the University of Georgia. “Sometimes the story is just the meteorology, not deficiency.”

The twisters were all on the weak end of the Enhanced Fujita Scale, the rating system for tornadoes that goes from EF-0 to EF-5. Both the worst New York and Oklahoma tornadoes were EF-2s, while the one in Salisbury was EF-1.

It’s these relatively weak, quick-to-spin-up, summertime tornadoes that can be extremely challenging for forecasters, as opposed to the huge monsters that tend to fire up in springtime. The storms literally pop up and go away in a few minutes, said Victor Gensini, a meteorologist and severe weather expert at Northern Illinois University.

These little spin up tornadoes can occur between radar scans, Schoor said, and are “almost undetectable.”

The tornadoes formed along what meteorologists call a quasi-linear convective system (QLCS), also known as a squall line.

Gensini emphasized that weather service employees overall do a “tremendous job,” as they issue hundreds of accurate warnings each year. “They do a great job with what they have.”

Schoor added that for every Hamburg tornado, “there are many cases where the warning system works and many people’s lives were saved.”

by Doyle Rice

August 14, 2017