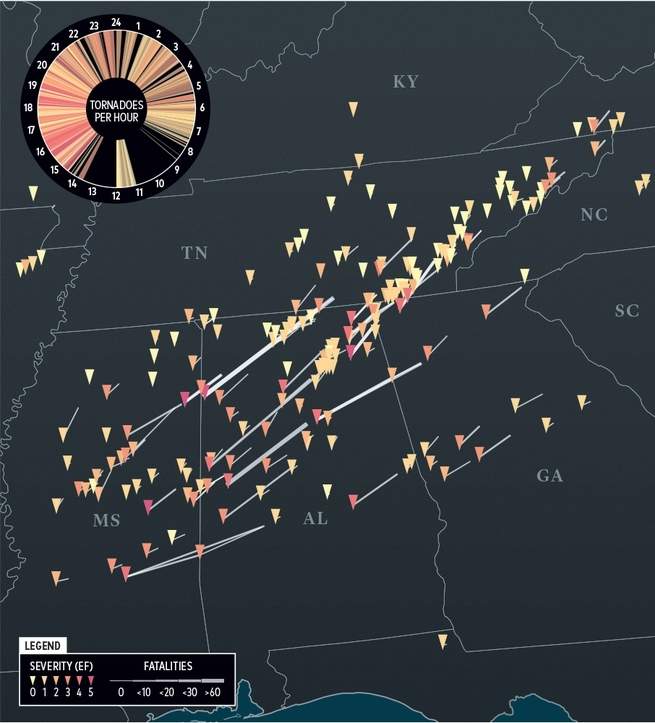

In 2011, an outbreak—not of disease, but of tornadoes—slammed through a large swath of the Southern and Eastern U.S. The region saw 64 individual twisters on April 25, and another 50 the next day, but the worst still lay ahead. A head-spinning 199 tornadoes touched down on April 27, killing 316 and injuring almost 3,000. To compare this cluster to others, meteorologists use the Destruction Potential Index. DPI is the sum of each individual storm’s destructive capacity, which weather-folk quantify by multiplying each tempest’s wind power by the area it hits. April 27’s outbreak reached 21,980. That’s three times the next-most devastating event in 2010.

Disasters like these are getting worse. From 1954 to 1963, the average outbreak—a sequence of six or more F1 or greater tornadoes that begin within six hours of each other—contained 11.4 storms. Half a century later, that number had risen to 16.1. Researchers are working to determine which weather and climate factors drive the clobbering hordes, but they can’t be certain quite yet. What we do know is that it’s increasingly likely we’ll have a day like the one mapped out above again.

By Sara Chodosh (2019, Jan 8) Popular Science